Photo by monicore from Pexels

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our necessities but of their advantages.”

– Adam Smith, ‘The Father of Economics’, in The Wealth of Nations

“Everybody’s doing it. In capitalism, you try to get the highest price you can for a product.”

– Martin Shkreli, convicted fraudster

By Ed Heskins, Senior Pricing Consultant at Pricing Solutions, and Luke Smith, Strategy Consulting Director at Iris

When a Price Increase Is Actually Price Gouging

When Adam Smith was developing his “invisible hand” theory of market equilibrium, he probably wasn’t thinking about toilet paper. Had he wandered through your local supermarket last week however, and seen the aisles of empty shelves, picked bare by nervous shoppers preparing for imminent isolation, even he would have recognised it as a market failing to respond adequately to a great shock.

How should markets (and the businesses that operate in them) respond in a crisis? Adherents of Mr Smith would argue that price increases in this instance are not only appropriate, but beneficial. If the price of a roll of toilet paper rocketed, surely only those that really needed it would still purchase? If fewer people stockpiled as a result, demand would be constrained so that in the short-term enough remained on the shelf for those actually running low, and in the long-term more suppliers would enter the market to improve availability (or alternative solutions would be found). It’s an old argument, resurfacing recently (see: The Telegraph ), which argues that anti price-gouging legislation, designed to protect consumers, actually harms them by allowing supplies to run out at below optimal prices.

Despite this argument, price gouging remains highly controversial. “Scheming thieves, profiting off death”, is how one local paper described reports of 200% price increases in Ilford, UK, this past week. Meanwhile, across the United States, Attorney Generals have declared their willingness to prosecute any person or business suspected of breaching price gouging laws. Even businesses that stop short of breaking the law, but who are seen to be using a crisis to drive profitability, can come under heavy criticism.

Dynamic Pricing & Customer Perception

Yet in many ways, the forces at play here are commonplace. Some businesses have long embraced dynamic pricing, (the idea that prices should respond to fluctuations in demand), including ride-sharing app Uber.

“Surge pricing automatically goes into effect when there are more riders in a given area than available drivers. This encourages more drivers to serve the busy area over time and shifts rider demand, to maintain reliability and restore balance.” – Uber.com

Sure enough, when New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio last week urged locals to stop using the subway over Covid-19 concerns, prices for Uber (and rival firm, Lyft) surged in response as commuters switched away from mass transportation options. According to Uber, surge pricing helps increase supply, encouraging drivers to clock on, ensuring that rides are always available for those who absolutely need them. It’s the same for airlines and hotels, who have used dynamic pricing for years to manage demand for their services.

Unlike other businesses, the response to Uber’s continued use of surge pricing has been more muted. Aside from some early complaints, Uber’s customers seem to understand surge pricing, to believe that the strategy works and above all, that it is fair. When prices surge, even in a crisis, customers accept it. Whether or not customers think your price increase is justified will depend on what kind of business you are. Or, more accurately, what kind of business they perceive you to be.

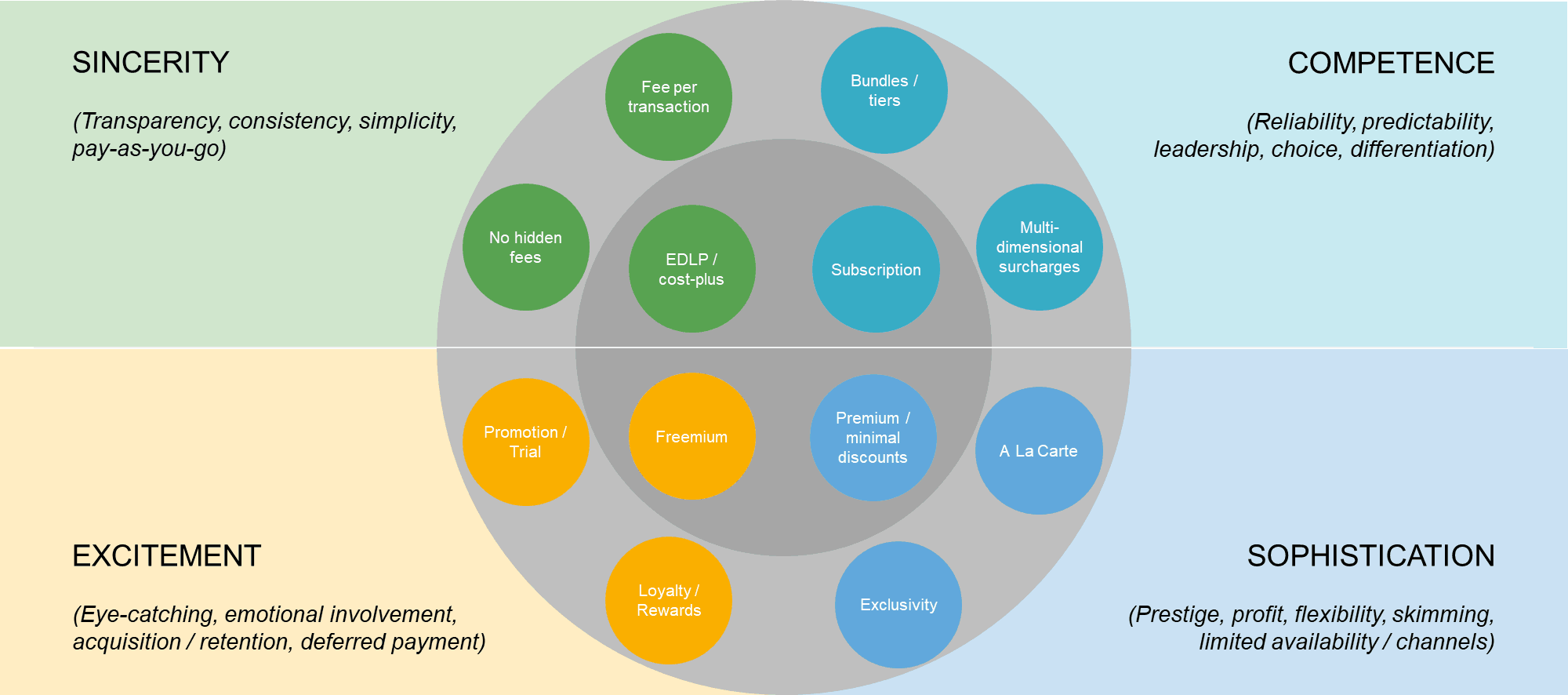

Above: the infographic demonstrates how different types of pricing offers evoke various perceptions among customers

In our analysis, businesses that are perceived to rely on perceptions of ‘Sincerity’ or ‘Competence’ tend to have less dynamic pricing models than those who rely on perceptions of ‘Excitement’ or ‘Sophistication’. Unsurprisingly, in markets where customers expect consistency or reliability, price changes are unwelcome, but they can be tolerated in markets with more emotional or prestige-linked value drivers. This relationship explains why customers tend to object to demand-driven price rises in some industries, and not in others. (No prizes for guessing where supermarkets and toilet paper manufacturers sit). Understanding how your business is perceived is the first step to formulating a price response.

Impact on Brand & Loyalty

It’s also important to realise, this is not a one-shot exercise. Your customers today may well continue to be your customers when the crisis is over.

With non-essential shops now shutting their doors for business, consumers are faced with limited choice. People will begin to shop at non-preferred supermarkets, for example, out of nothing more than necessity, meaning retailers have an opportunity to keep these customers after the crisis is over. But how? Under normal circumstances, we know that customer experience is a key differentiator , and whilst this still rings true in times of crises, being a purposeful brand is also going to drive commercial growth in the long term. According to recent studies in Asia, brands that ‘deliver purpose in an ethical way’ will grow twice as much as average brands.

There have been numerous examples of brands showing an understanding of their place in society, such as Pret offering 50% off for NHS workers and Sainsbury’s launching a dedicated shopping hour for the elderly and vulnerable, not to mention the abundance of marketing emails from CEOs demonstrating compassion for their employees’ health and financial wellbeing.

In industries such as retail, travel, leisure and hospitality, where business has either slowed right down or trading has ceased completely, they must find a way to continue to play a role in people’s lives.

The Future Is Now

However, it is important that brands realise that this is an ongoing process. When faced again with greater choice in the future, will consumers really remember the actions some brands took at the start of the crisis and make this their number one criterion, ahead of price, quality and convenience? Whilst we would like to think this is the case, and nobody can say for certain, it is likely that some old consumer purchasing habits will exist in the future.

Therefore, there has never been a better time for businesses to pivot and innovate, by creating new products, propositions, business models and revenue streams, ideally addressing the needs of customers in the current crisis (where possible), whilst also preparing them for the future. Whilst we can’t predict when this crisis will end, it is becoming increasingly hard to see that society returning to ‘normal’ when it does, with consumer expectations, priorities and product choices all going to change enormously.

In our analysis, businesses that are perceived to rely on perceptions of ‘Sincerity’ or ‘Competence’ tend to have less dynamic pricing models than those who rely on perceptions of ‘Excitement’ or ‘Sophistication’. Unsurprisingly, in markets where customers expect consistency or reliability, price changes are unwelcome, but they can be tolerated in markets with more emotional or prestige-linked value drivers. This relationship explains why customers tend to object to demand-driven price rises in some industries, and not in others. (No prizes for guessing where supermarkets and toilet paper manufacturers sit). Understanding how your business is perceived is the first step to formulating a price response.

Impact on Brand & Loyalty

It’s also important to realize, this is not a one-shot exercise. Your customers today may well continue to be your customers when the crisis is over.

With non-essential shops now shutting their doors for business, consumers are faced with limited choice. People will begin to shop at non-preferred supermarkets, for example, out of nothing more than necessity, meaning retailers have an opportunity to keep these customers after the crisis is over. But how? Under normal circumstances, we know that customer experience is a key differentiator , and whilst this still rings true in times of crises, being a purposeful brand is also going to drive commercial growth in the long term. According to recent studies in Asia, brands that ‘deliver purpose in an ethical way’ will grow twice as much as average brands.

There have been numerous examples of brands showing an understanding of their place in society, such as Pret offering 50% off for NHS workers and Sainsbury’s launching a dedicated shopping hour for the elderly and vulnerable, not to mention the abundance of marketing emails from CEOs demonstrating compassion for their employees’ health and financial wellbeing.

In industries such as retail, travel, leisure and hospitality, where business has either slowed right down or trading has ceased completely, they must find a way to continue to play a role in people’s lives.