Original Source: The Drum

By: Ed Heskins, Head of Pricing, Europe, Iris Pricing Solutions

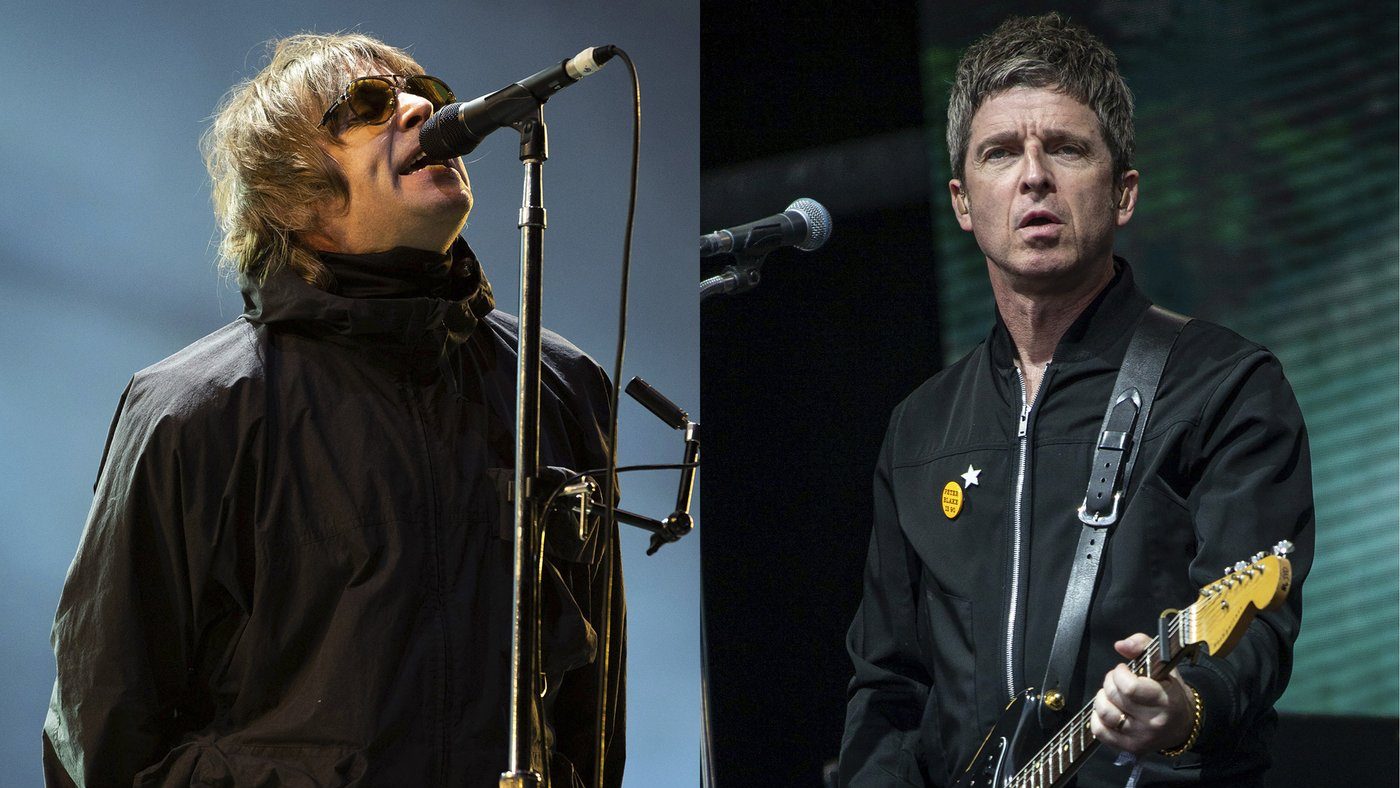

When Liam and Noel Gallagher, the enfants terrible, feuding brothers and poster children for the 90s Britpop movement, announced that they had set their differences aside long enough to take the band on tour again, fans were thrilled. For summer 2025, 17 major dates were announced at outdoor venues in the UK, with worldwide dates still to follow.

Knowing that stratospheric demand was sure to outstrip supply, many fans prepared military-like operations, deploying multiple laptops and phones and corralling friends and relatives to ensure they would have the best chance of securing tickets, which went on sale last Saturday (and subsequently sold out).

But this initial excitement turned to disappointment and anger when having queued online for upwards of six hours to secure tickets, fans arrived at the (virtual) ticket office to find that tickets were now being listed at many multiples of their original quoted sales price. A standing ticket that had originally been listed at £150 was now only available for £355, a 136% increase in price in less than a day.

Fans and commentators were quick to point the finger at the bogeyman suspected to be responsible for this: dynamic pricing – which is my bread and butter so stand by me while I explain.

What is dynamic pricing?

Once the preserve of data wonks and pricing geeks, discussion around dynamic pricing has become more and more widespread in recent years, often to the annoyance of consumers.

Dynamic pricing is the process of adjusting prices, in real-time, based on the level of demand a product or service is experiencing. It allows businesses to respond quickly to spikes (and dips) in anticipated demand, ensuring that profits are maximized and demand is distributed appropriately across products, time periods, or geographies.

Most commonly, it is used in businesses where supply capacity is fixed and time-bound, eg, hotel rooms, airline flights, and now concert tickets. This is important because, unlike goods with a longer shelf-life, there is a fixed point in time when these products cease to have value (after all, who wants to buy an airline ticket for a flight that already took off?) Managing demand so as to exactly meet supply is, therefore, a very profitable exercise for these businesses.

The benefits to the businesses employing dynamic pricing are obvious. Why sell out a flight that is experiencing high demand at a lower price when you can sell out the same flight at a higher ticket price and make more money?

So far, so cynical.

But are there benefits to consumers as well?

Well, sometimes. And sort of.

By raising prices on one flight, airlines are able to shift demand around by identifying customer groups whose travel plans are more flexible. A family of four may curse the higher school holiday prices at their hotel, but raising prices now increases room availability by ensuring that their suites are not sold to holidaymakers who could perfectly well travel at other times of the year.

A customer looking to book an Uber during peak times may see the inflated prices and decide to walk or take public transportation instead, leaving more cars available for customers for whom this is not an option.

For Uber and other services business models, the argument is also supply-driven.

By increasing fares at busy times, they can encourage drivers who may not be planning to work to change plans and take advantage of “surge pricing” to generate some extra income. This means more cars available when and where they’re needed.

Dynamic pricing, then, increases choice and access for consumers.

So in a way, the high price of £355 for a standing ticket attracts Oasis into the supply… but is it a a good deal for consumers? Well, no. Not exactly…

Stop crying your heart out

There are many things that define whether a pricing strategy can be successful for consumers, and dynamic pricing depends on two elements in particular: transparency and choice.

First, transparency.

The pitfalls of dynamic pricing in retail have long been discussed, and a general consensus has been reached: the price that a consumer sees when they make a decision to purchase should be the same as the price they pay when they are able to complete that purchase. A shopper cannot pick an item off the shelf, finish their shopping, then pay a different price at the till. Clearly, waiting six hours in a queue to buy tickets at one price and then being charged an entirely different price fails this test. It is unsurprising that fans would react negatively to such an experience.

Second, choice.

At its heart, all price segmentation, including dynamic pricing, is about offering choice to consumers. Would I fly a day earlier or later if the price was significantly cheaper? Can I move my holiday to an off-peak month? Would I accept a standing ticket over a seat in the upper bowl if it meant receiving a discount? In the case of Oasis, it appears that ticket prices were increased across venues and tiers so that consumers were only left with a choice between different heavily inflated ticket prices, no matter how flexible they were prepared to be. Again, a negative consumer experience.

Additionally, while the debate around dynamic pricing often centers on short-term profits and supply-demand mechanics, the broader implications for brands cannot be overlooked.

In an age where consumer loyalty and brand reputation are more valuable than ever, businesses must carefully balance revenue maximization with maintaining trust and goodwill. Pricing is no longer just a financial decision – it’s a critical aspect of brand strategy. How fans and customers feel about their purchase experience can have long-term effects on brand perception, and those negative feelings can easily overshadow the initial excitement. Oasis, like many brands, faces the challenge of ensuring that short-term gains don’t come at the expense of long-term loyalty.

Finally, concerts – much like sporting events – should be conscious of the extent to which their audience are part of the live experience. For better or worse, an Oasis concert played to an audience who have paid in excess of £700 for a pair of standing tickets is going to be a different live experience than playing to an audience of £150 sales. High ticket prices come with high expectations, after all.

What next for dynamic pricing?

Legislators across both the US and the UK have announced they are “looking into” the practice.

What realistic restrictions they can place on it is unclear at this point. Price gouging legislation already covers the pricing of necessities, but concert tickets are discretionary purchases. No one (other than perhaps the exhausted parents of teenage music fans) is obligated to buy tickets if they feel the price is unfair. If Oasis want to maximize the amount of money they make from their fans (possibly at the expense of that relationship), they are free to do so. It certainly doesn’t seem to have hurt Taylor Swift’s reputation (or bank balance).

But ultimately the use or misuse of dynamic pricing will rest with the businesses looking to employ it. For many businesses, more dynamic pricing models will not be acceptable for their customers. Customers may prefer reliability of budget, or they may not feel the benefits of flexible pricing are fairly distributed.

In these situations, fans (and customers) are free to start a revolution from their bed and, in doing so, put pressure on businesses to rethink their pricing practices. They might even find a better place to pay.

In the meantime, is dynamic pricing likely to be around to stay? Definitely/Maybe.