Keeping the Right Customers

Why are long-term customers so lucrative? Because they generally buy more, pay more, cost less to service, make referrals, and cause fewer bad debts. New customers, on the other hand, do not generate a profit the first year due to acquisition costs, but pay increasing dividends in subsequent years.

A long-term customer is a profitable one, but customer loyalty must be systematically managed before it can be improved.

A long-term customer is a profitable one, but customer loyalty must be systematically managed before it can be improved.

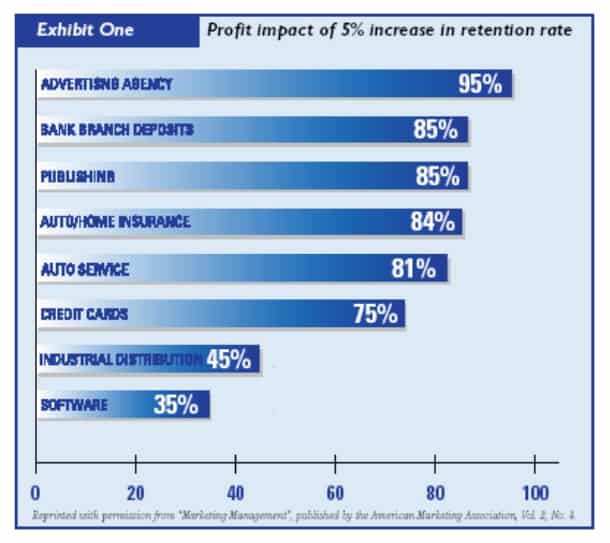

Psst! How would you like to increase your profits by at least 25 — and maybe even 100 — percent? Who wouldn’t! But in fact, any business can achieve this lofty goal, simply by improving its customer retention rate. Studies show that a mere five percent increase in retention rate can boost corporate profits anywhere from 35 percent in the software industry to a whopping 95 percent for advertising agencies (See Exhibit 1.)

Why are long-term customers so lucrative? Because they generally buy more, pay more, cost less to service, make referrals, and cause fewer bad debts. New customers, on the other hand, do not generate a profit the first year due to acquisition costs, but pay increasing dividends in subsequent years.

But not all customers are worth keeping. Organizations must define and attract the right customers — those who will remain loyal over the long haul. New customers who are lured by price discounts seldom become long-term clients, as they can be easily lured away by someone else’s promotional gimmick. General Motors acknowledged this when it established its Saturn division several years ago. It was among the fi rst to implement a “no-dicker sticker price” within the dealer network to discourage those notoriously disloyal price shoppers.

Whatever efforts an organization puts into managing customer loyalty, it must be able to measure the results. After all, you can’t improve what you can’t measure. But current satisfaction measurement systems may not be enough, as keeping customers is not necessarily the same as keeping customers satisfied. In fact, according to a 1993 article in Harvard Business Review, titled “Loyalty-Based Management,” a certain percentage of customers who defect say they were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their former supplier. In other words, a satisfied customer is not necessarily a loyal one. Finding — and keeping — loyal customers means taking a long, hard look at the kinds of customers to whom a company can deliver superior, lasting value. The following article discusses some of the tools that will help businesses do just that.

The Tools

The true measure of customer loyalty is repeat business. But in order to keep those coveted customers coming back for more, an organization must be able to deliver value to them over the long term. Four tools to help a company achieve this goal are: defection analysis, buying behavior analysis, complaint handling, and zoning customers.

Tool #1: Defection analysis

An organization that is managing toward zero defections naturally must analyze why customers leave. Just as an airline uses a ‘black box’ to determine what went wrong, companies, too, can use failure analysis to improve their operations.

For example, when one of our clients — a bank — lost one of its major international clients to a competitor, there was much disagreement in the ranks over the cause. “To get to the root cause of the defection, we met with the bank’s former client,” says Paul Hunt, President of Pricing Solutions. “During the interview we learned many things which had a significant impact on the buying decision, of which our client was unaware. For example, the customer indicated that they wanted a more senior operations person involved in the negotiations, yet our client perceived that the person they had

involved was senior enough. Meanwhile, the competition sent in their most senior operations people, giving them a substantial advantage and playing an important role in the difference between retaining and losing that account.” Part and parcel of defection analysis is determining what customer retention

means for each organization and industry. On the surface it may appear to be simple to identify customers who have defected, however this is not always the case.

For example, if a customer is spending less on their Visa card than before, it could be due to several different reasons. If the person lost their job, then Visa management would not define this as a defection; but, perhaps the customer is spending less because they are now using an additional credit card, obviously a defection. Clearly defining what a defection is is not always easy.

Tool #2: Buying behavior analysis

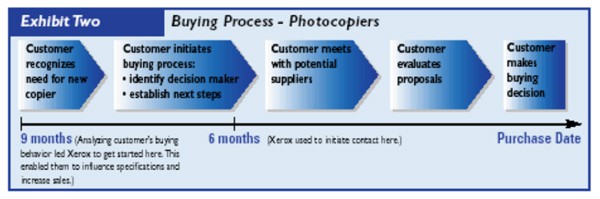

Aspiring loyalty-based companies must analyze not only defections, but also buying behavior, by mapping out the buying process by segment and identifying key points of decision. This exercise paid off handsomely for Xerox Corporation when it conducted a study of its selling cycle. (See Exhibit 2.) Previously, the company communicated with its customers about six months prior to the time they would normally buy their next copier. However, it discovered, to its surprise, that customers initiated the buying process about nine months before making the purchase. Therefore, in order to influence

the buying decision, Xerox realized it had to communicate with its customers nine months in advance, rather than six. What a difference three months can make!

Similarly, a consulting fi rm knew that people usually bought its product every two years. What it didn’t know, however, prior to conducting the buying behavior analysis, was that it needed to promote the product to customers a year in advance, when they were doing their budgeting.

Once the buying process has been identified, companies must develop a communications program with customers that respond to those key decision points.

Tool #3: Complaint handling

Customers who voice a complaint are twice as likely to repurchase, if the complaint is resolved to their satisfaction. Therefore, a complaint should be viewed, not as a problem, but as an opportunity to gain a loyal customer.

In order to convert a dissatisfied customer into a loyal client, however, a process must be in place to make it easy for customers to lodge their complaint. Toy manufacturer Fisher Price, for example, provides a toll free number with all its products. If a customer calls to complain about a particular product, the company replaces it almost immediately, free of charge. Now that’s service!

A follow-up procedure should also be established, to ensure the complaint does get resolved. For its Part, Pizza Hut follows up on any complaints with a phone call. It immediately rectifies the problem, and then calls the customer again to confirm that the company has met his or her expectations. The effort pays off in spades. Pizza Hut estimates that the average customers spend about $14,000 over his lifetime on pizza – an investment well worth protecting.

Tool #4: Zoning customers

As the fourth building block to customer retention, a process of “zoning” customer loyalty is recommended. This simply means using a predictive model to identify how loyal a customer is. “Typically, you categorize each customer as a level one, two or three, with one being the most loyal and three the least loyal,” explains Hunt. “You develop criteria to determine whether or not a customer is loyal, and then zone that customer accordingly. But changes in a client’s circumstances can directly impact whether you will retain them as a customer. For example, if a buyer with whom your company has a long-standing relation is transfer, that customer would drop a level because of uncertainty over the new buyer. Or perhaps the customer is experiencing financial difficulties. That would also cause it to drop a level, simply because the funds for purchasing your product may no longer be available. Having identified this, prompt corrective actions can be taken.”